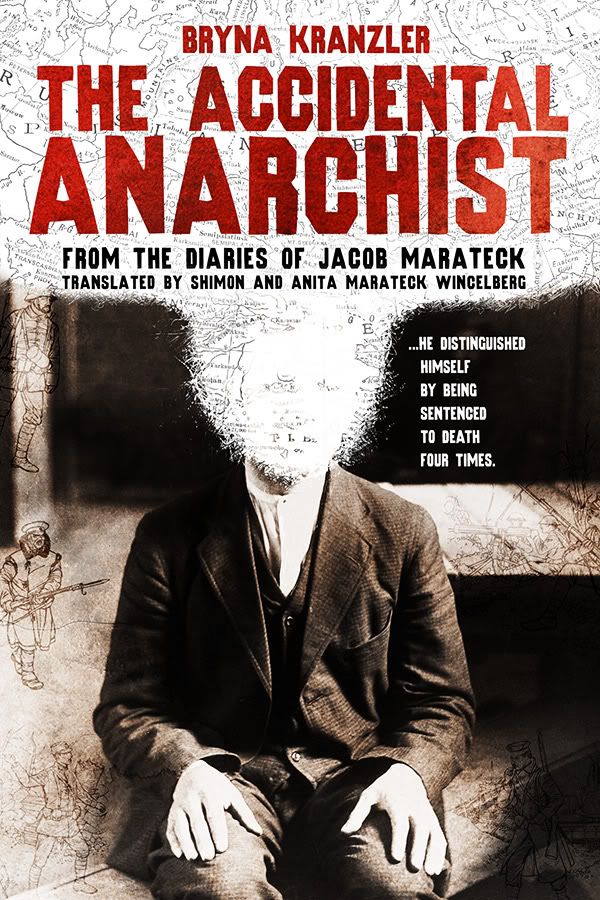

I mentioned that I was busy. Yes, I've been working with the book jacket designer, a talented graphic artist who happens to be in Russia, and an astute editor who happens to be in Australia. (It's not a small world; it's a virtual world). I'm pleased to report that soon the graphic designer will be working on the layout of the text -- 'soon' being as soon as I stop working on it. While I was pleased to learn that my editor said that the book is a fun, fast-paced read, there are still areas that need work, and that's where my focus has been. I've also been tracing my grandfather's route from Petersburg to the various battlefields in the war, making sure that the information I have is in the correct order, according to which battle to place where and when, and in which direction they were moving at the time (the latter mostly pertains to the escape from Siberia).

Meanwhile, I thought it was time to share the story of my grandfather's fourth death sentence, which came closest to execution (pun) than all the previous ones. As all of this will be in the book, I'm posting only portions of that information here.

Background: Following his return from the Russo-Japanese War, my grandfather and many others were thoroughly disillusioned with the Russian government (where anti-Semitism was an official policy) and its inept army. While he had wanted to launch a revolution before the war (and many believe that the Russo-Japanese War was prompted by Russia to distract the populace from their dissatisfaction with their government -- sound at all familiar . . ?) he returned even more determined to upset the social order and overthrow the Czar.

Once he was back in Warsaw, the first order of business was deciding which of the many revolutionary parties to join. Since my grandfather had earlier been involved with the Bund, a Jewish Socialist Party, he was quickly invited to rejoin them, without pay (much as my college graduate son has been getting great opportunities to work for nothing during this recession). The following is from his experiences with the Bund:

I was sent on various, strange errands. To keep them properly cloaked in secrecy, each mission was organized in a manner so melodramatic that any policeman with half a brain should have collared the lot of us within the first half hour.

One morning, I was summoned to the Bristol Hotel, a place ordinarily out of my class. I saw from a distance that its lobby was densely populated with Czarist agents.

My assignment was to make contact with someone holding one end of a broken match; I was to carry the other half. After confirming that our pieces fit together, the man would say to me in Polish, “Excuse me, sir, can you give me a light?” To which I would reply, “What brand of cigarettes, sir, do you smoke?”

It did no good to point out that such a dialogue would be hard to mistake for a casual exchange between two normal human beings. To make things worse, I was given a piece of the wrong match, meaning that each of us would arrive carrying half a match without a head. My handler agreed there may have been a slipup, but it was too late now to alter the arrangements.

Picture two shabbily dressed strangers circulating in the crowded lobby of this elegant hotel, stooping over, from time to time, to gaze at what each other person held between his fingers. After sweating through I don't know how many minutes of this little minuet, my contact and I finally noticed each other’s peculiar behavior, and sheepishly flaunted our headless matches. We then recited our stilted passwords and managed to walk out together, all without arousing the suspicions of our excellent police force.

In the street, my fellow plotter, a jittery, young man with bad skin, kept looking over his shoulder. Half a block away, when he finally felt it was safe to talk, said, “Are you prepared to go on a mission?”

“What kind of a mission?”

He yanked me into a doorway. “I can't tell you.”

”Then I'm not going.”

“All right,” he said grudgingly. “Delivering supplies.”

“Supplies of what?”

Scowling with annoyance, he mumbled, “Ammunition.” His tone let me know I had no business asking such an idiotic question.

While the task sounded harmless enough for someone of my background, I knew of several comrades who had been arrested while transporting such goods and, with very little fuss, sentenced and shot.

But my contact allowed me no time for reflection, snapping, “Wait here,” as he vanished across the street.

Trapped, I loitered in plain sight of the Bristol, straining to look invisible and braced, at any moment, for a heavy hand to fall on my shoulder.

Instead, I saw a tall young woman make her way daintily through traffic. Flustered, she stopped near me and looked around. This, I assumed, was my new contact since one would have had to be blind not to have spotted her instantly as a man in a poorly fitted horsehair wig. Nor was he too cleanly shaven.

I tried to lose myself among the passing pedestrians, hoping this person in a pavement-trailing skirt and high-heeled boots would not be able to follow me.

But the creature in the wig caught up with me. Smiling through smudged lips, he motioned coquettishly with his finger. Resigned, I allowed him to capture my elbow and summon a droshky. We climbed in, and he directed the driver to a certain number on Shliska Street. The driver cracked his whip, giving no sign of having noticed that his orders came from a woman with a rather hairy voice.

We pulled up at a shoemaker’s cellar where my contact, with the nonchalance of a commercial traveler on an expense account, ordered the droshky to wait, as if we had not been warned time and again that some cab men also served as police informants.

A minute later, I staggered back out into the street hauling two valises so heavy that one of the handles promptly came off in my hand. My load crashed to the pavement.

At this, the shoemaker turned white, and then became hysterical. Hopping up and down, he cursed my clumsiness and consigned me to the seven depths of hell. I realized that I was not carrying mere bullets but a more nervous kind of merchandise, like dynamite or homemade bombs, the kind we cozily called “dumplings,” some of which had been known to go off at inconvenient times.

Still in his wig and padded dress, my contact ordered our driver to take us to a windowless shack outside the city and deep in the woods where, to my relief, a refreshingly businesslike couple accepted delivery of the supplies.

To Be Continued

"Lady Thatcher's Finest Hour" is se in the Bristol Hotel in Warsaw. It's one of the chapters in "High Times at The Hotel Bristol", a book of short stories based on hotels around the world called Bristol: see http://bristolhotels.blogspot.com

ReplyDelete